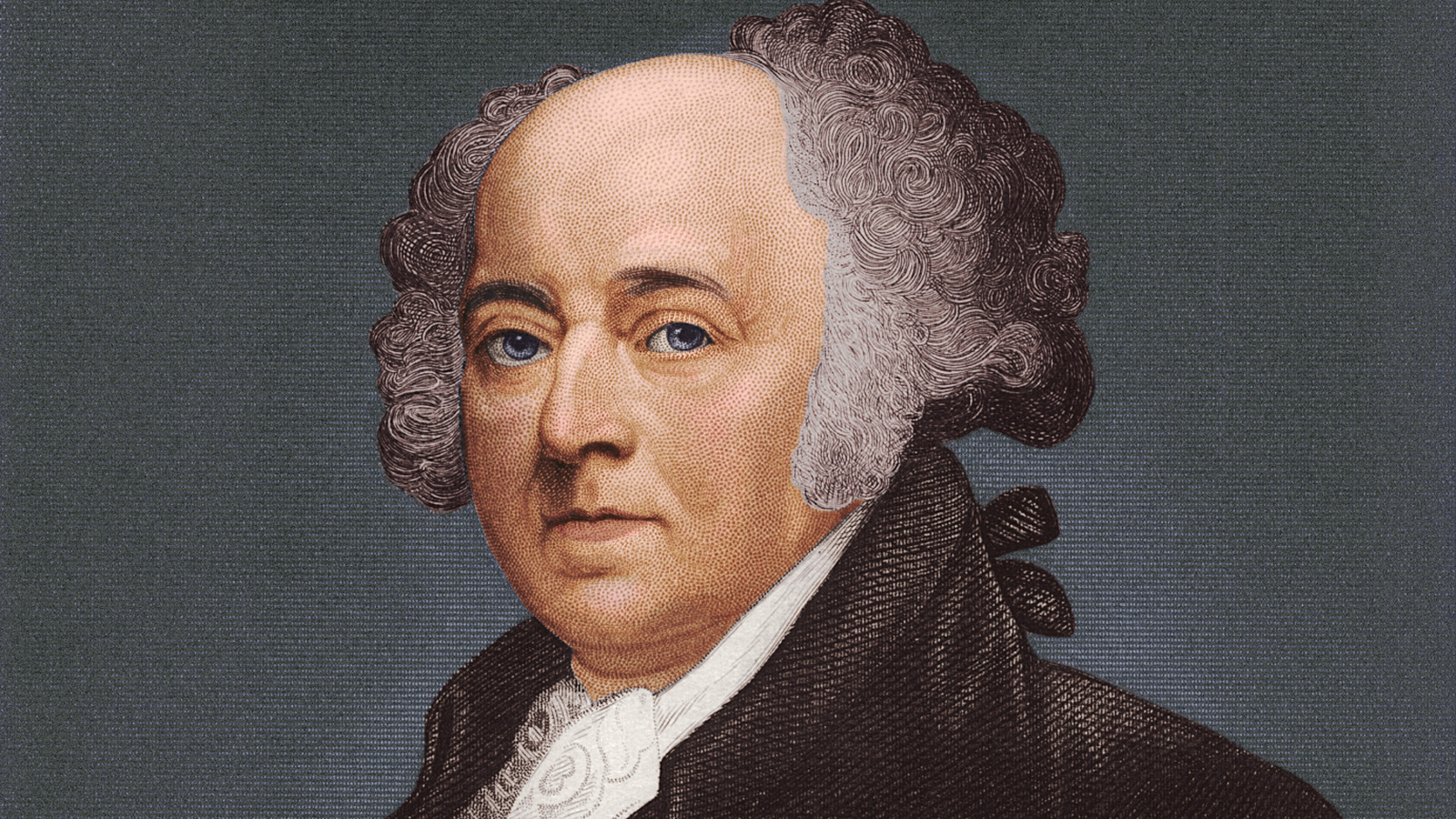

Among his many accomplishments, John Adams wrote the 1780 Massachusetts constitution, signed the 1783 Treaty of Paris, and served for three years in the Continental Congress, before becoming the first U.S. Vice President and second U.S. President. But he wasn’t just a legendary democratic thinker — like many of his political predecessors and civic successors, Adams was also a legendary drinker. While Andrew Jackson sipped on whiskey punch, George Washington poured glasses of wine, Franklin Delano Roosevelt would champion the dirty martini, and John F. Kennedy would mix up daiquiris and bloody marys, Adams preferred a simple New England classic. Throughout his adult life, he held a nearly fanatic fondness for hard cider.

In fact, he would reportedly begin most of his mornings with cider for breakfast. By some accounts, he began the habit in his college days, swigging a “gill” of cider (about 4 ounces) to start his day — and according to his 1796 diary, he either continued the habit into or picked it back up in his sixties. Even apart from this daily routine, Adams was seemingly devoted to the drink, regularly mentioning it in his letters and receiving barrels of it as gifts. It wasn’t just cider’s crisp refreshment he had a taste for, though; Adams believed that hard cider carried health benefits.

An apple (cider) a day keeps the doctor away

Harvard University, the second president’s alma mater, was a useful source of anecdotal evidence for John Adams’ healthy cider argument. In correspondence with Harvard professor Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse, Adams linked declining health at the school to changing fashions around alcohol consumption, with students’ imbibing spirits and wine rather than cider. He insisted that during his own scholarly tenure at the college, the students drank much less wine and spirits and much more cider — and thus, there were no student deaths while he was there. Adams connected long, healthy lives to hard cider consumption, and chose the drink himself above nearly all others, because he claimed it was the only liquor that wasn’t detrimental to his health (even admitting in his later years that he only ever drank water, lemonade, and cider).

Although Adams’ medicinal cider rhetoric was based largely around experiential evidence, there have been scientific studies supporting the health benefits of cider. Fermented apple juice contains polyphenols, a class of compound found in many different types of plants that have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Polyphenol-rich diets and even the fermentation process that creates cider have been linked to prevention of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

Cider in the annals of alcohol history

When the United States was still a fledgling country, alcohol of all kinds played an important part in culture. Communities and revolutions were forged in taverns, and politicians racked up enormous bar bills to celebrate victories, bond with constituents, and satiate their fanaticism for certain spirits (George Washington’s infamous love for Madeira wine once contributed to a single farewell party’s bar tab that would be the equivalent of $15,000 today). Cider in particular was essential to the country’s history. European settlers brought apple seeds with them, and apples became some of the first crops planted by Europeans in the New World — and later cultivated by Indigenous and enslaved peoples. Before the generations of cultivation gave us varieties similar to those we know today, many apples from these trees had a bitter taste and would be fermented into hard cider instead of eaten.

Because the colonists’ available water sources were often hazardous, cider was also a safer alternative to the drinking water, and when colonists produced apple cider vinegar, they could also pickle other foods to keep them safe and preserved. In many parts of the early U.S., where the apple bounty was plentiful, cider’s popularity eclipsed other alcohols and non-alcoholic beverages. Demand for hard cider may have declined in modern times, but during the Revolutionary Era, John Adams was hardly alone in his fondness for it.